War

War (and rumors of war) are everywhere. We live in a world with many reasons for losing hope. Now feels like one of those moments. Please don’t lose hope.

Everywhere is war

Me say war

War in the east

War in the west

War up north

War down south

War, war

Rumors of war

-Bob Marley, “War”

War (and rumors of war). Russia-Ukraine. Israel-Gaza. Civil wars in Sudan, Myanmar, Ethiopia and Nigeria. The conflict between Israel (and possibly the US) versus Iran is escalating quickly.

In my work as a mediator, I’ve seen violence, hatred, anger, greed, poverty, and hopelessness and war. I often feel overwhelmed by the intense suffering that so many people carry. We live in a world with many reasons for losing hope.

Now feels like one of those moments.

Please don’t lose hope.

When conflict escalates to a point where people resort to taking up arms, launching missiles, destroying communities, and advocating for the dispossession or elimination of entire groups of people, the thought patterns I frequently encounter from individuals involved in the conflict and those adjacent to it look like this:

There is a right side and wrong side

I need to take a side

The people on the other side are not like me

Violence from my side toward their side is justified

Violence from the other side toward my side is not justified

Peace is only possible through violent force in times like these.

If you are not with me, then you are against me

I see these predictable patterns running the gamut from family to international conflict. Social psychologists and theologians have been writing about them for ages, and there are reams of academic studies that predict these seven thought patterns that typically lead to behaviors with horrific outcomes.

We know where thoughts and attitudes like this lead and what their outcomes are likely to be. Nevertheless, when the war is over, we will stand back and ask ourselves, “How did this happen?” We will vow never to let it happen again. And then, with enough time and provocation, we will do it again.

We know that wars disproportionately affect women, children, and the poorest of the earth — the very people least likely to start them or care about them — while at the same time arguing that we are raising a banner of freedom to protect our homes, our families, our communities, and our most vulnerable.

While there may be moments in history where war has been inevitable, it was almost always preventable, and deciding when it is justified is almost always clouded by these flawed thought patterns and poor decision-making fueled by a sense of fear and self-preservation.

It is especially hard for me to see my fellow Christians fall into these belligerent attitudes when Jesus has offered us a different way to navigate the conflicts that we face. Jesus too faced intense political, religious, cultural, and economic conflict. Many of his followers wrestled with the same seven attitudes we see today. They were often frustrated by what Jesus taught and at times dismissed it as being unrealistic or even dangerous.

War can provide us with the peace we desire, whether it’s feeling strong or protected. However, it fails to deliver the peace we truly need—the peace of reconciliation and the building of the beloved community.

Jesus offered us the peace we need, not the peace we want.

In the midst of so much fear, anger and uncertainty, I want to remind you of that today with a modified chapter from Seventy Times Seven that explores a serious, violent conflict in Missouri between Missouri citizens and immigrants from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I pray it provides some context for the types of questions we wrestle with today and some understanding about how we might approach questions of war, self-defense and power from the perspective of Jesus. Most importantly, I pray it offers hope in times that feel so hopeless.

Power and Influence (a modified excerpt from Chapter 4 of Seventy Times Seven)

It’s one thing not to throw the first stone. It’s another thing entirely not to pick up stones and hurl them at our enemies when our enemies are throwing them at our heads.

Jesus commands, “Do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also” (Matthew 5:39). Although some have interpreted it as a call for passivity, Walter Wink translates the command as proactive:

“Don’t strike back at evil (or, one who has done you evil) in kind. Do not retaliate against violence with violence. . . Don’t react violently against the one who is evil. The only difference was over the means to be used: how one should fight evil.”[i]

In the film Gandhi, Gandhi tells a Christian minister, Charlie Andrews, that Jesus’s call to turn the other cheek is meant to be taken literally.[ii]

“I have thought about it a great deal,” Gandhi tells Andrews. “I suspect [that Jesus] meant [that] you must show courage, be willing to take a blow, even several blows, to show you will not strike back, nor will you be turned aside; and when you do that, it calls on something in human nature, something that makes his hatred for you decrease and his respect increase. I think Christ grasped that, and I have seen it work.”[iii]

Does Jesus want us to get slapped in the face? Repeatedly? His followers were understandably worried about the first blow and the subsequent blows that an enemy might strike if they turned the other cheek.

That was the question Joseph Smith and the members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints living in Missouri wrestled with after violence drove them from their homes in the 1830s. Church members were killed, and Joseph, Sidney Rigdon, and others were imprisoned in a tiny cell in Liberty, Missouri, facing a likely sentence of death for treason.

Cold, starving, sick, and cramped in a dark, damp, filthy prison cell, Joseph cried out to God, like David in the Psalms, asking for divine help for himself and the Latter-day Saints. He begged for vengeance against those who had committed wrongs against him and his people.

O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place? How long shall thy hand be stayed, and thine eye, yea thy pure eye, behold from the eternal heavens the wrongs of thy people and of thy servants, and thine ear be penetrated with their cries?

Yea, O Lord, how long shall they suffer these wrongs and unlawful oppressions, before thine heart shall be softened toward them, and thy bowels be moved with compassion toward them?

Let thine anger be kindled against our enemies; and, in the fury of thine heart, with thy sword avenge us of our wrongs. Remember thy suffering saints, O our God; and thy servants will rejoice in thy name forever. (Doctrine and Covenants 121: 1–3, 5–6)

Things had gone horribly wrong for Joseph and the thousands of followers who had converted to the faith. After years of excitement and growth, the members of the Church were facing intense destructive conflict.Many members of the Church were refugees, needy, and afraid. It appeared that everything they had worked for had failed.[iv]

This story is critical to understanding Jesus’s admonition to practice 70 x 7. Sometimes, we throw stones to control and seek retribution, vengeance, and justice when we have been wronged and are afraid. When we believe and act like God will show us mercy and favor while showing hatred and vengeance toward our enemies, we are walking the path of destructive conflict.

The teachings of Jesus can provide us a way out of all this pain and misery.

The Law of Retaliation and Forgiveness

Five years before Joseph was imprisoned in Liberty, he was dealing with the first signals that things weren’t going smoothly in Zion. Early Latter-day Saint settlers had migrated to Jackson Country, Missouri, after Joseph was commanded through revelations to build Zion. Zion would be a gathering place for the Saints and where Jesus would return at the beginning of the Second Coming.

Historian Richard Bushman, in his book Rough Stone Rolling, lays out the series of events that led to Joseph's imprisonment in Liberty Jail. It starts here. The revelation calling for gathering to Missouri used the word “enemies” to describe the current residents, and indeed they were becoming so. The Latter-day Saints spoke of the land being redeemed by its rightful inheritors. The Evening and Morning Star wrote matter-of-factly about “tak[ing] possession of this country.”[v]

Emboldened by revelation that seemed to guarantee them a place of refuge and power, conflict between the Latter-day Saint settlers and Jackson County, Missouri, residents flared within a few months. As tension grew with the Missourians, Joseph started gathering a makeshift army to defend the Latter-day Saints. In August 1833, Joseph received a revelation that became section 98 in the Doctrine and Covenants. In this revelation, God explains how to respond to injustice.

If men will smite you, or your families, once, and ye bear it patiently and revile not against them, neither seek revenge, ye shall be rewarded.

If your enemy shall smite you the second time, and you revile not against your enemy, and bear it patiently, your reward shall be an hundred-fold.

And again, if he shall smite you the third time, and ye bear it patiently, your reward shall be doubled unto you four-fold. (D&C 98:23, 25, 26)

If the conflict continues, God tells them that the perpetrator is to be warned again (D&C 98:28). If the conflict continues after all these peacemaking attempts, only then would the Latter-day Saints be “justified” to “rewardest him according to his works” (D&C 98:31). Nevertheless, the Lord promises that “if thou wilt spare him, thou shalt be rewarded for thy righteousness; and also thy children and thy children’s children unto the third and fourth generation” (D&C 98:30).

Often, when discussing section 98, it’s easy to jump past all the calls for non-violence and peace and quickly get to the justification of violence and retribution. In verse 31, a victim is only justified in rewarding his enemy “according to his works” after multiple attempts to renounce war and proclaim peace.

However, the focus of Doctrine and Covenants 98 and Jesus’s teachings in the New Testament are proactive admonitions to love our enemies, to forbear, to forgive, and to continue to seek peace, even when our enemies pursue war. In the brief mention of the justification for violence (D&C 98:31), God clarifies that justification is not sanctification. While a victim may be justified in returning violence for violence, it’s not pleasing to God. Continuing to sue for peace is God’s preferred model.[vi]

God goes even further in verses 38 through 48, emphasizing forbearance and forgiveness, even when an enemy doesn’t repent. God urges the Saints to bring the unrepentant to God and, after all of that, if there is no repentance, the matter is to be left entirely in the hands of the Lord (see D&C 98:38–48). The section even uses the language of Jesus in Matthew, imploring Joseph to forgive his enemies, “until seventy times seven” (D&C 98:40).

I think all this emphasis on forbearance, repentance, forgiveness, and patience reminded Joseph and the members of the Church of something hard to see when trapped in conflict: their enemies were sons and daughters of God, too. God desired their salvation and happiness as much as he did theirs.

Forbearance, repentance, forgiveness, and patience are hard enough to practice with family members or others we know well. Even the people closest to us are sometimes hard to love. Rolling away stones with respect to the people we love, let alone our enemies, is challenging. It becomes infinitely more complicated when 70 x 7 must be practiced more broadly with strangers, people, or groups we don’t know or have never met.

We may be justified, after a time, to retaliate against those who hurt us. But retaliation does not further the work of God. It causes enmity and blame. It may feel good, but its fruits don’t bring salvation for either the avenger or the avenged. On the other hand, love invites a turning of stony hearts into fleshy ones. It invites both victim and victimizer to Jesus. It may be challenging, but it is the only path to sustainable peace.

Hyrum Mack Smith and Janne Mattson Sjödahl wrote a commentary on section 98 in 1923 that summed up the message aptly:

As the world is constituted at present, it is impossible to live in it without being wronged some time. What to do, when wronged, is one of the great problems of a Christian life. The world says, “Get even!” The Master says, “Forgive!” “Absurd!” the world exclaims, “What are laws and courts and jails for?” Christ bids us remember that our worst enemy is, after all, one of God’s children whom Christ came to save, and that we ought to treat him as we would an erring brother. Very often, Christian love in return for a wrong proves the salvation of the wrongdoer. It always has a wonderful effect upon those who practice it. It makes them strong, beautiful and God-like, whereas hatred and revenge stamp, upon the heart in which they dwell, the image of the devil.[vii]

For a time, Joseph and other Church members followed God’s counsel. But it didn’t take long for their patience to wane. Upon hearing about his people’s plight, Joseph wrote in a letter that he was driven nearly to “madness and desperation.”[viii] Joseph prayed that his enemies would “go down to the pit and give pl[a]ce for thy Saints.”

A few days later, he wrote that he was ready to respond to the violence with more violence if God would give the go-ahead: “We wait the Comand of God to do whatever he plese and if <he> shall say go up to Zion and defend thy Brotheren by <the sword> we fly and we count not our live[s] dear to us.”[ix]

Members of the Church were suffering and baffled that God had not defeated their enemies. It wasn’t long before the revelatory guidance in section 98 faded into the fog of war. By November of 1833, the Latter-day Saints were exchanging fire with the Missourians. When two Missourians were killed in the exchange, it unleashed more violence as the Missourians began to believe that the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were intent on “butchering us all.”[x]

Latter-day Saints fled Jackson County to Clay County. However, a similar pattern emerged as Missourians complained about their new neighbors’ insular behavior, political beliefs, and strange religious practices. Latter-day Saints were forced to leave their homes again in 1836 at gunpoint.

Even after agreeing to settle in Caldwell County, a new county set aside only for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, violence continued. As more and more settlers arrived, Joseph began purchasing property in neighboring Daviess Country and Carroll County, raising the alarm again of a Latter-day Saint takeover, and violence escalated to war. Driven by fear and ignorance, the Missourians did horrific things. People were murdered and raped. Homes were burned. Vexatious lawsuits multiplied. Even though the Latter-day Saint settlers tried to follow section 98 briefly, many eventually chose vengeance.

On July 4, 1838, Sidney Rigdon, the first counselor in the First Presidency of the Church, delivered a fiery speech and promised “. . . a war of extermination, for we will follow them, till the last drop of their blood is spilled, or else they will have to exterminate us: for we will carry the seat of war to their own houses, and their own families, and one party or the other shall be utterly destroyed.”[xi]

Some Latter-day Saint historians have argued that Rigdon’s speech was meant to de-escalate, not escalate the conflict. They believe Rigdon “deliberately formulated [the speech] to comply with the requirements of” Doctrine and Covenants 98. Specifically, they argue that Rigdon’s speech was an attempt to “solemnly warn” the enemies of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as required by Doctrine and Covenants 98:28. If the warning (which The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saint Church went to great pains to publish and distribute) went unheeded, the Latter-day Saints would be “justified” to “rewardest him according to his works” (D&C 98:31).[xii]

In an August 1838 editorial, Joseph Smith wrote that given the history of displacement, the Latter-day Saints could not and would not be relocated again. He reiterated that if the warning were ignored, the Latter-day Saints would not “be mobed any more without taking vengeance.”[xiii]

Unfortunately, some Missourians saw Rigdon’s “warning” as a threat and a significant escalation in the conflict: “Missouri newspapers regularly cited it in subsequent months as evidence that the Saints meant to defy the law and wage war against other Missouri citizens.”[xiv] Fearing for their own lives, Missouri citizens formed militias and began attacking Latter-day Saints settlers in Daviess and eventually Caldwell counties. In October 1838, forty Latter-day Saints were massacred at Haun’s Mill, and Joseph surrendered to the Missouri militia to prevent any more bloodshed.[xv]

Joseph, Rigdon, and several others were arrested, court-martialed, and almost executed on the spot. The prisoners were eventually sent to Liberty Jail to await trial. It is there that Joseph, beaten, exhausted, and on the verge of death, pleads with God for redemption in a letter excerpted in Doctrine and Covenants 121.

What War Is Good For

Once we begin to hate our enemy, instead of loving them, we begin to feel that throwing stones is justified, and the conflict escalates. I call this a conflict tornado.[xvi]

The way we see others influences how they see us, and how they see us influences how we see them. When we no longer love our enemies as brothers and sisters in the human family, we start throwing stones, which, in turn, invites them to see us the same way, fueling an escalating spiral into conflict that often leaves us dumbfounded on how we got to such a horrible place. [xvii] Once the conflict tornado starts spinning, several predictable patterns emerge.

When we see our brothers and sisters as enemies in conflict, our tactics in conflict transition from soft (e.g., compliments or debates) to hard (e.g., threats and force).[xviii] The issues we fight over also shift from small ones (e.g., “You left your socks on the floor!”) to big ones (e.g., “I’m not sure you ever loved me!”). Our goals shift from changing others or winning to hurting those we conflict with even if these actions hurt us, too. Conflicts also tend to increase in size from two individuals to entire families, organizations, or even nations.[xix]

Conflict escalation generally follows two models: the contender-defender model and the conflict spiral model.[xx]The contender-defender model occurs when one person is pushing for change while the other person is primarily in a defensive position.[xxi] The conflict spiral model (or the conflict tornado) happens through a series of actions and reactions. Each party keeps escalating the conflict in reaction to the other party escalating the conflict.[xxii]

Most of the people I work with think they are stuck in a contender-defender model: the person they are in conflict with is the aggressor and they are playing defense. Or, if they started the conflict, they justify their actions by claiming they are only intervening for the other person’s good. Both patterns are evident in Joseph’s letters and Rigdon’s speech as violence escalated between Church members and Missourians. “The more innocent we think we are and the guiltier we think the other side is, the more we feel justified in doing things in the name of ending a conflict that only exacerbates it.”[xxiii]

The contender-defender model is the proper explanation for what’s going on in some cases of conflict and can explain some of the early conflicts the Latter-day Saints settlers faced in Missouri. We can be victims and be acting in a purely defensive manner. However, what happened in Missouri eventually grew into a conflict tornado.

Practicing 70 × 7 teaches us that we are part of the pattern of conflict. Just because our opponent struck first doesn’t take away our choice about what we do next. Everything depends on it. What we do next will powerfully influence how others see us and choose to respond. If we strike back, a full-blown conflict tornado is likely to result. If we turn the other cheek, it becomes harder for a conflict tornado to arise or sustain itself. The more we practice 70 × 7, the harder it is for our enemies to maintain enmity. And enmity fuels conflict tornados.

That is what God explains so eloquently to Joseph in section 98 and perhaps what Rigdon, Joseph, and others got wrong by relying on Doctrine and Covenants 98:31’s justification for retaliation after solemnly warning their enemies instead of relying on Doctrine and Covenants 98:30’s promise that “if thou wilt spare him, thou shalt be rewarded for thy righteousness; and also thy children and thy children’s children unto the third and fourth generation.”

It is hard to see that we are feeding and keeping a conflict tornado alive. It is hard to have the courage to change. For those like me who stumble on the path of Jesus’s way, it is easy to justify throwing stones. There have been times when I want God to help me fight, to help me overpower my enemies, and to tell me that I am right and they are wrong. While the desire to stop evil and injustice might be good, does returning evil for evil, hate for hate, and violence for violence ever really look like Jesus’s way?

Too often, my heart has been at war, or I’ve felt hopeless against a stampede of hate. I, like Joseph, have felt shocked and overwhelmed by the call of 70 × 7. To “renounce war and proclaim peace” in our families and personal relationships is hard enough (Doctrine and Covenants 98:16). In the face of the most complicated, most complex, and long-lasting conflicts of our time, Jesus’s call for 70 × 7 truly feels audacious.

Proclaiming peace has never been easy. Following Jesus’s example has actual costs. Renouncing war and proclaiming peace like Jesus will be inconvenient at best and often feel downright dangerous.

The Influence of Love

Joseph’s plea for vengeance in Liberty Jail after all the suffering he and his people had endured is very human. Joseph pleads with God to soften his heart and have compassion toward Joseph and his people while simultaneously asking God to “Let thine anger be kindled against our enemies; and, in the fury of thine heart, with thy sword avenge us of our wrongs” (Doctrine and Covenants 121: 3, 5). His plea can be outlined like this: Mercy for us and justice for our enemies.

God promises neither vengeance nor force. He calls Joseph, once again, to renounce war and proclaim peace. God begins, “My son, peace be unto thy soul” (D&C 121:7). This greeting may seem like a small thing. But I think it’s one of the first keys to understanding section 121. When we are engulfed in fear, our responses to conflict typically make things worse, not better. We become blinded to the humanity of those with whom we are in conflict and simultaneously blinded to how our responses to conflict make the situation worse.

The parts of our brains that we need to creatively problem-solve shut down. With large planks in our eyes, our moral imagination fails us. We often end up doing the opposite of what will help us. We lose sight of how Jesus sees us and our opponents, and we start looking for stones to throw.

God starts by comforting Joseph. He promises that the pain will end and that joy is coming. He reminds Joseph about his friends, validates his pain, and later promises him pure knowledge that will greatly enlarge the soul (D&C 121:42).

God creates a safe space for Joseph to see things the way God sees them, even though Joseph is suffering physically and spiritually. He pours out love despite Joseph’s mistakes. He does not punish. He rolls away stones. That’s important because the pure knowledge God will offer Joseph and the Saints will almost be impossible to hear from a space of fear. He tells Joseph that if he can feel enduring peace, he will triumph over all his enemies (D&C 121:8).

God then assures Joseph that those who lack charity towards him and the Saints will suffer the consequences of their actions. Failing to live in Jesus’s way comes with natural consequences. God says that they will be blinded because of their hatred and that the pain they intend to inflict on others “may come upon themselves to the very uttermost; that they may be disappointed also, and their hopes may be cut off” (Doctrine and Covenants 121:13–14). They can expect that:

Their basket shall not be full, their houses and their barns shall perish, and they themselves shall be despised by those that flattered them. They shall not have right to the priesthood, nor their posterity after them from generation to generation. It had been better for them that a millstone had been hanged about their necks, and they drowned in the depth of the sea. (Doctrine and Covenants 121:20–22)

I don’t think God is promising Joseph that He will punish the people who vex the Latter-day Saints. I believe God is saying that these calamities are the natural consequences of choosing war instead of peace. There is an intergenerational cost to hate, mistreatment, and violence. All those involved in conflict suffer these consequences.

In the next few verses, God discusses judgment, damnation, and hell. Anyone caught in the middle of a conflict tornado knows exactly what these things feel like. Joseph’s desire for God to exact vengeance on his enemies will not bring the peace that Joseph thinks it will. Instead, revenge brings more pain and stops us from moving on with our lives. “The power he wants to see wreaked on others is the wrong kind of power,” writes James Faulconer, “God warns him where the demand for that kind of power will lead, to an ‘Amen’ to personal growth toward godliness.”[xxv]

Jesus’s way is different; Doctrine and Covenants 121: 33–46 lays it out powerfully. True power doesn’t come from military or heavenly might. It comes from love. It comes from living the second great commandment. The power of the priesthood cannot rest on control or dominion.

Behold, there are many called, but few are chosen. And why are they not chosen? Because their hearts are set so much upon the things of this world, and aspire to the honors of men, that they do not learn this one lesson—that the rights of the priesthood are inseparably connected with the powers of heaven, and that the powers of heaven cannot be controlled nor handled only upon the principles of righteousness.

That they may be conferred upon us, it is true; but when we undertake to cover our sins, or to gratify our pride, our vain ambition, or to exercise control or dominion or compulsion upon the souls of the children of men, in any degree of unrighteousness, behold, the heavens withdraw themselves; the Spirit of the Lord is grieved; and when it is withdrawn, Amen to the priesthood or the authority of that man.

Behold, ere he is aware, he is left unto himself, to kick against the pricks, to persecute the saints, and to fight against God. We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion.

Hence many are called, but few are chosen. (D&C 121:34–40)

These verses have historically been read as a rebuke toward the people who betrayed Joseph. It’s a fair reading. However, I don’t think the counsel here is limited to Joseph’s enemies. There is a lesson to be learned here for Joseph, his followers, and us today.

Joseph and the Latter-day Saints had indeed been called. But had they been chosen? The power they wished to wield against their enemies was powerless when used without love. And while establishing Zion by obtaining land and a safe place to gather was essential to God, how they obtained those things mattered. To paraphrase Gandhi, the means are the ends in the making.[xxvi]

The heavens withdraw when we are proud, vain, and ambitious, when we lack the humility to admit to and repent of our sins, when we collect and throw stones, and when we try to use force or compulsion. Our relationship with God is extrinsic, not intrinsic, in our stone-throwing moments. God becomes nothing more than a weapon for us to wield.

In section 98, God gave Latter-day Saints the game plan to righteously triumph with their enemies—not triumph over them, but triumph with them. While there were well-intentioned attempts to follow the counsel in section 98, fear, frustration, anger, and the need to protect themselves took precedence. The heavens withdrew. By fighting their enemies, they were fighting against God, for God had commanded them to love their enemies because their enemies, too, were his children.

Given the fear and suffering the Latter-day Saints experienced in Missouri, that they failed to endure in practicing 70 × 7 is understandable. I have failed, repeatedly, with much less provocation than they faced. I do not mean to judge them. However, it is important to understand why their endeavor to build Zion failed. Zion is a place where people dwell “in righteousness” with “no poor among them,” united with “one heart and one mind” (Moses 7:18). Zion will not grow out of violence.

For Zion to be established and for the blessings of heaven to flow the way the Saints expected, we have to follow Jesus’s way. And this is the way:

No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned; by kindness, and pure knowledge, which shall greatly enlarge the soul without hypocrisy, and without guile—reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost; and then showing forth afterwards an increase of love toward him whom thou hast reproved, lest he esteem thee to be his enemy; that he may know that thy faithfulness is stronger than the cords of death.

Let thy bowels also be full of charity towards all men, and to the household of faith, and let virtue garnish thy thoughts unceasingly; then shall thy confidence wax strong in the presence of God; and the doctrine of the priesthood shall distil upon thy soul as the dews from heaven.

The Holy Ghost shall be thy constant companion, and thy scepter an unchanging scepter of righteousness and truth; and thy dominion shall be an everlasting dominion, and without compulsory means it shall flow unto thee forever and ever. (Doctrine and Covenants 121:41–46)

Jesus’s way is persuasion, patience, kindness, meekness, and pure knowledge. What is the pure knowledge that God refers to? I’ve read several excellent explanations. I want to offer another one:

Pure knowledge comes when I understand that my enemy is a child of God; that Jesus atoned for their sins, like he did for mine; that the worth of my enemy’s soul is equal to my own; and that to be a disciple of Jesus is to know this, deep in our bones, to the point that we are filled with compassion and love toward those who struggle to see us the way God sees us.

The purest knowledge I can think of is seeing each of us the way God sees us. This change of heart gives us the courage to overcome whatever fear holds us back from loving the way he loves. This is the pure knowledge we need to practice 70 × 7. I believe seeing others this clearly is also a key to understanding what it means to reprove “betimes with sharpness.” James Faulconer’s reading of this verse is powerful.

If, after using gentleness, meekness, and unfeigned love to influence others, reproof is needed, it should be given early (the meaning of the word betimes) and with sharpness (v. 43). But does sharpness mean “severity” or does it mean “acuity”? I believe that the second meaning fits the context better than the first. We sometimes read verse 43 to mean “occasionally reproving severely, when the Holy Ghost tells us to,” but I believe it means “reproving early with acuity, when the Holy Ghost moves us to.” Reproof, too, must be gentle, meek, and a demonstration of unfeigned love—as God’s response has been to Joseph Smith’s complaint.[xxvii]

According to verse 43, any sort of reproving should be done with an increase of love so that whoever we give feedback doesn’t misunderstand it as an attack. They should feel the love coming from us so much that they know we are eternally faithful to them. Faulconer concludes, “That is what it looks like to have received the knowledge of God, the ability to act in our relationships with others as we see him acting in his relationships with us, in a faithfulness that is stronger than death, indeed so strong that it has overcome death in order to rescue us.”[xxviii]

This is the way Jesus works in our lives to heal all that afflicts us. As his disciples, we further his work toward the least of these by trying to do the same.

Hope

Now, you might say follow Jesus’s way is not practical. It doesn’t reflect the realities of my pain or the evil that exists in this dangerous world.

You might say that violence, hatred, destructive conflict, and evil will always be with us. Our best efforts at peacemaking will be blown back in our faces by the wind of opposition. If our hearts are broken and our spirits contrite, we’ll be vulnerable and trampled underfoot by those who wish us harm. We live in a world where an eye for an eye is the only language our enemies understand.

How can anyone have optimism in times like these?

All of us who have tried imperfectly to follow Jesus have had similar concerns. In my work as a mediator, I see violence, hatred, anger, greed, poverty, and hopelessness. I often feel overwhelmed by the intense suffering that so many people carry. We live in a world with many reasons for losing hope.

When a newspaper posed the question, “What’s Wrong with the World?” the Catholic thinker G. K. Chesterton wrote in response: “The answer to the question ‘What is wrong?’ is, or should be, ‘I am wrong.’”[xxviv]

Too often, I am failing. It’s not only the world or others. It’s me. I feel overwhelmed by the enormity of the call of 70 × 7. It is easy to become discouraged. I’ve experienced so much failure. I’ve struggled to forgive and to help others forgive. I’ve struggled to choose reconciliation. I’ve been part of more failed mediations and peacemaking interventions than I can count.

However, I’m also struck by another reality—less reported but equally valid. Amid these dangerous times, so much good is going on around us. Everywhere I go, even amid significant conflict, I am amazed at the charity, selflessness, and hard work others do to ease people's suffering.

Thousands of people work tirelessly every day to work with families who are struggling, to relieve poverty, help prevent and treat the devastating scourge of disease, attend to refugees, work for the civil and human rights of others, stop violence and war, and heal the victims of such atrocities. They risk their lives, health, and livelihoods to save thousands, even millions of lives.

Millions are doing Jesus’s work of restoration in their families and communities. Devoted parents patiently love their children through physical and mental illness. Others take in children from wounded families and help them feel loved and at home. They volunteer in organizations and do the holy work of healing the wounded and bridging divides.

In the Middle East, where I have spent much of my career working, even amid war, I’m constantly amazed at the number of people on both sides of the conflict who, despite often suffering immensely themselves, risk their lives and well-being in an attempt to bring peace.

I’ve seen miracles happen. I’ve seen people who were enemies work together to find peace. I’ve witnessed mercy, forgiveness, and the risk of embrace by individuals in some of the most intractable conflicts in the world.

Everywhere I turn, even amid so much pain, destruction, and chaos, I see the spirit of Jesus working through individuals partnering with him in that sacred and vital work or peacemaking.

People are on the move.

Love is on the move.

Peace is on the move.

God is on the move.

The question is are we going to be on the move with him?[xxvv]

Jesus calls all of us, the flawed and sinful, to be the peacebuilders the world needs. He’s calling you and me in his great work of restoration. It takes courage to answer, “Here am I. Send me!” (Isaiah 6:8).

To all of those who answer Jesus’s call to “come follow me” with “send me,” Jesus has a word for you: “Blessed.” The Greek word is makarioi, meaning “supremely blest.”[xxvvi] It is the ultimate form of blessing. Jesus promises to put a wind at your back and give you a rising road if you follow him. God will bless you, supremely.

So don’t lose hope.

Don’t fall into the thought patterns that lead to war.

Reverse them.

Instead ask:

How can I help all sides mired in destructive conflict?

How can I see the humanity in all sides of the conflict?

How can I practice non-violence in thought, word and deed toward the people I am in conflict with?

How do I embrace that peace is only possible through finding alternatives to violence in times like these.

How do I live into the idea that conflict can and should be constructive, even sacred. That conflict is a living relational space between us. In conflict there is no “me” or “them,” only “we.”

“Blessed Are the Peacemakers; For They Shall Be Called the Children of God”

Blessed are they who transform destructive conflict into constructive conflict.

Blessed are they who create space for the eyes of our hearts to be enlightened.

Blessed are they who persuade us with lovingkindness to roll away our stones.

Blessed are they who open their arms and embrace us, even when our hearts are still at war.

Blessed are they who are willing to risk their lives and dedicate themselves to the sacred work of restoration— at home and everywhere else where peace does not exist.

Blessed are they who see through conflict to Jesus’s ultimate truth: All of us are children of God, and God wants to bring all His children home.

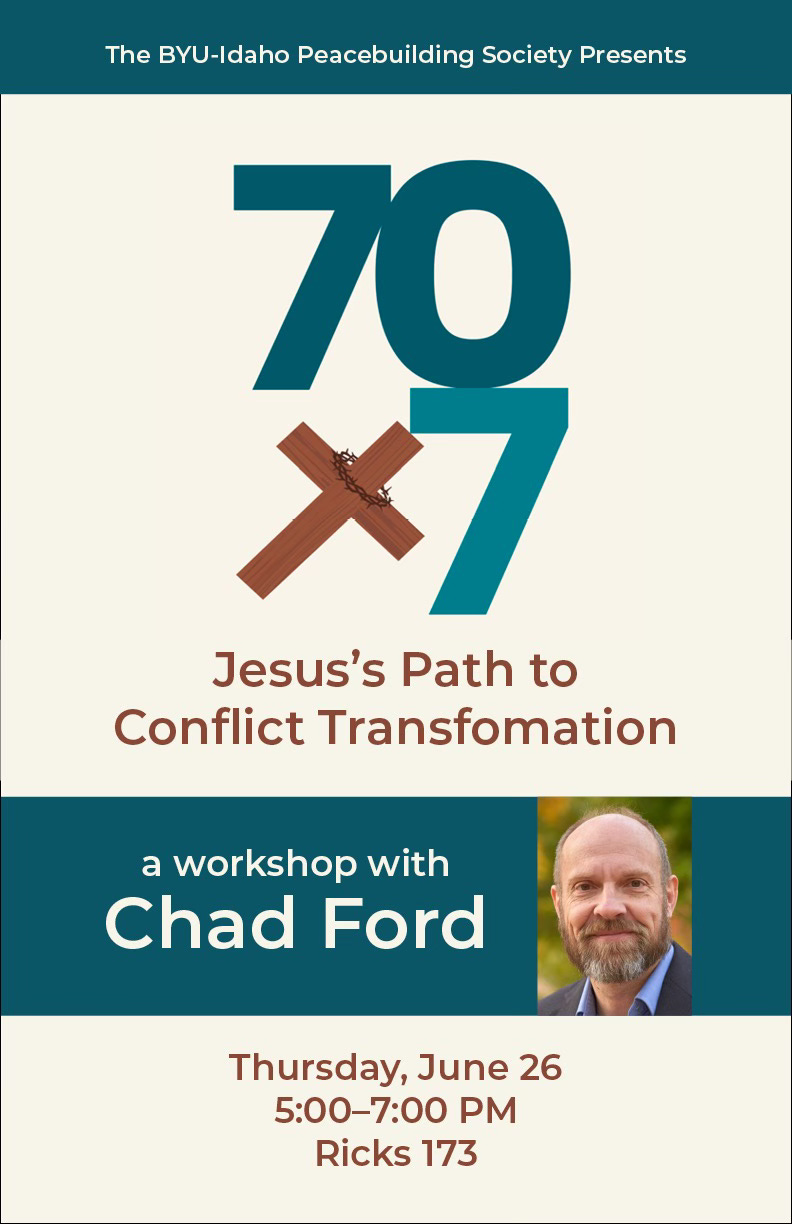

70x7 in Idaho next week

I’ll be in Rexburg, Idaho for two events on Thursday, June 26th.

The first is a lecture entitled “The Peace We Want vs. The Peace We Need” and it takes place on BYU-Idaho’s campus, RICKS 173 at 11:30.

The second is a workshop where I will use some of the principles from 70x7 to help participants navigate a conflict they are wrestling with in their own life. That two-hour workshop will be from 5 pm to 7 pm in RICK 173 on BYU-Idaho’s campus.

All are welcome to attend!

I can’t imagine anything more terrifying or more beautiful than this radical approach to conflict that you so powerfully describe. So terrifying as to cause even Jesus Christ to plead for another way. So beautiful as to transform death into rebirth and brokenness into at-onement. May it become that which is most true in our own lives and in our world!

Everything in me says yes this is the way.