I met Pastor Jamie White at an event last year for faith leaders wrestling with how to prevent suicide in their faith communities.

I opened the event with a workshop and she closed the event with a sermon and both of us delivered, essentially, the same message:

Conflict is exile. Peace is return.

Pastor White quoted from two texts in the Old Testament. The first was from Jeremiah where he gives surprising counsel to a group of people who were in bondage, in deep conflict and separated from their home.

“Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce … Increase in number there; do not decrease. Also, seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile. Pray to the Lord for it, because if it prospers, you too will prosper.”

“...I will come to you and fulfill my promise to bring you back to this place. For I know the plans I have for you…plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” (Jeremiah 29: 4-8, 10-14)

The lesson from exile? How we see conflict and how we respond to exile has a powerful effect on what happens next. Not all conflict needs to be contention. Not all conflict needs to end in despair or destruction.

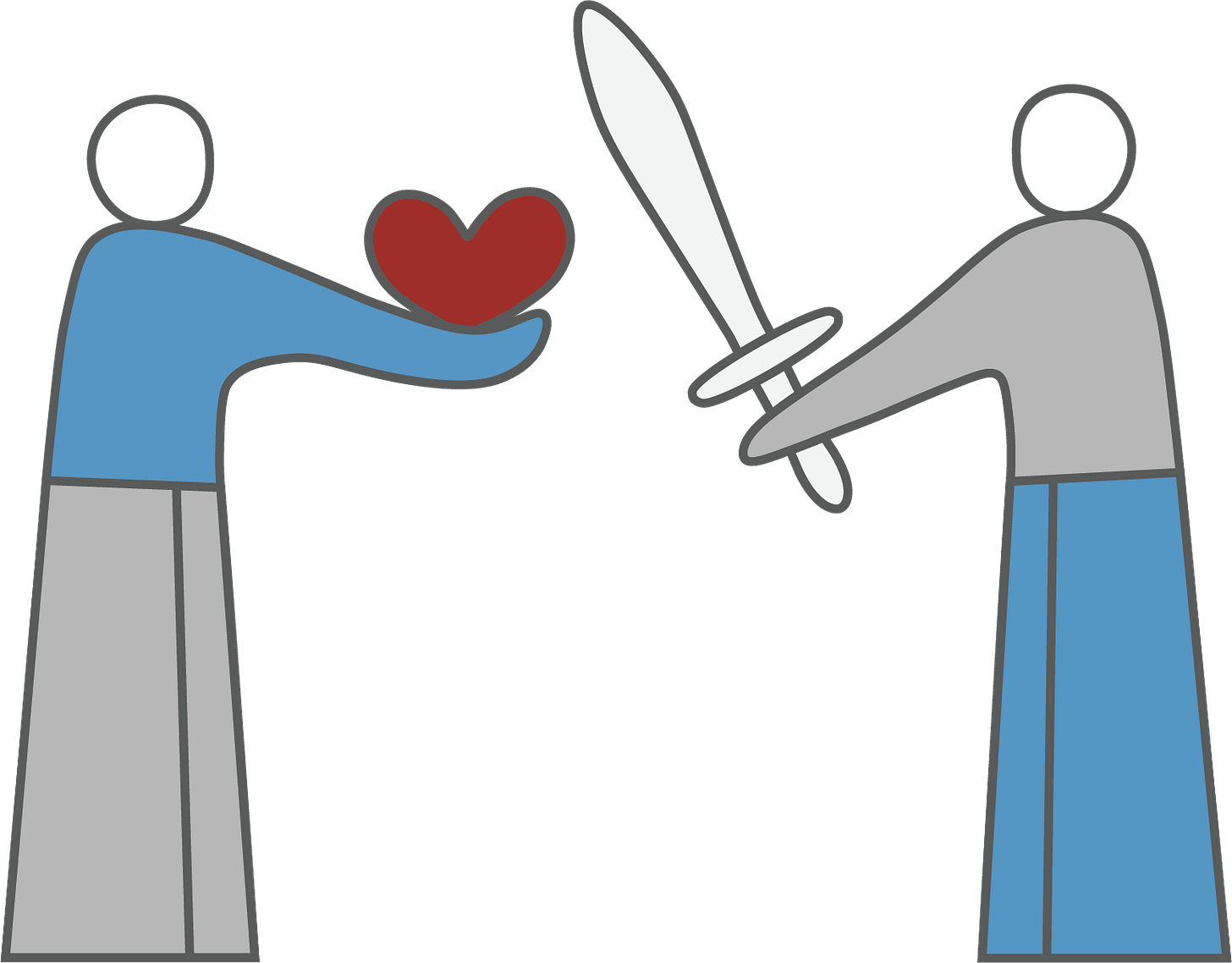

Conflict can also lead to joy, to prospering, to improved relationships. It may not seem like it when we are in the middle of things, but conflict creates, it inspires and it promotes powerful change.

None of us knows home, belonging or return — tangible or spiritual —without struggle. And struggle teaches us to tread more softly, more courageously, more forgivingly through our hurting, hoping, heart breaking, heart opening, life.

Exile points us home. We shouldn’t fear it. We should embrace it and let it show us the way. It is exile that creates space to imagine a restoration – not just replicating what once was, but a new creation.

Pastor White ended her sermon with a verse from the book of Ezra after those same people that Jeremiah spoke to were allowed to return from exile. As the priest laid the foundations of a new temple on top of the one that had been destroyed, the prophet Ezra commented that the people were simultaneously weeping and shouting for joy and “No one could distinguish the sound of the shouts of joy from the sound of weeping, because the people made so much noise. And the sound was heard far away.” (Ezra 3:13).

I would come to find out later that Pastor White’s deep thoughts about exile and return come from hard earned experience. As a young woman, Pastor White would sit on her bed with clenched fists, repeating, “I will forgive. I will forgive.” The choice to forgive, as Jamie shares in this video, “Loving your Enemies” is a choice to re-enter life after being transformed by tragedy.

In our latest Where Peace Begins video, Pastor White tells her story and it is one of the most powerful sermons I’ve heard on the power of loving our enemies. Note: this video contains discussion of sexual assault. Though the story shared is one of resilience and transformation, viewer discretion is advised.

Jamie shares, powerfully, how Jesus’ example has guided her reconciliation process.

There’s a lot of things Jesus didn’t say. There’s a lot of questions he did not answer. However, he did talk a ton about love. And he said a lot about loving our enemies. And then he showed us what it looked like: he laid his life down. And none of that looked like weakness. Every single time, it looked like incredible strength. And it didn’t make anyone afraid of him. It made everyone want to be near him. And people got whole, and healed.”When Jesus invites us to love our enemies, the Greek word for love that Jesus uses is agape.

In King’s masterpiece, Strength to Love, he notes that the Greeks had three different words for what the English language calls “love.”[i] The first type was called eros and referred to romantic love. Eros is sensual. It is yearning. The second Greek word for love was philia. It’s the love you feel toward a friend or family member for whom you have affection. These two types of love describe caring for someone we like and who likes us back. Those are not the sorts of emotions that most of us feel when in conflict. The third word is agape. King writes that agape is

. . . understanding and creative, [the] redemptive goodwill for all men. An overflowing love that seeks nothing in return, agape is the love of God operating in the human heart. At this level, we love men not because we like them, nor because their ways appeal to us . . . ; we love every man because God loves him. At this level we love the person who does an evil deed, although we hate the deed that he does.[ii]

Agape is the Greek word for love used in Luke 10. Agape-love is the best way to describe seeing another person's humanity so clearly that their needs, wants, and desires matter as much to me as my own. Agape moves the Samaritan not only to put his own life in danger to care for the dying man but also to excessive altruism. He binds the wounds of the “certain man” on the road, transports him to a safe place, and uses his resources to secure his long-term care.

According to King, the Samaritan “reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”[iii] I call that love “dangerous love,” a love that overcomes fear in the face of conflict. Nothing is “safe” in dangerous love. Dangerous love requires more than courage: it demands fearlessness.

Theologian Adam Miller writes, Jesus “died to rescue sinners. Love like this—love for an enemy in open rebellion—is an even greater kind of love. This love cost Jesus his life, but it also saved us from the wrath that accompanies sin.”[iv]

Dangerous love transforms conflict by calling upon us to let go of our instinct for self-preservation triggered by fear: “What will happen to me if l let down my walls and help the person I’m in conflict with?” Dangerous love demands that we embrace us-preservation: “What will happen to us if I don’t?” When that sort of love takes hold, our views of ourselves, others, and the conflict transform. We no longer see enemies or others in conflict. We see “us.” The eyes of our hearts are enlightened. It takes that level of personal transformation in the face of conflict, this level of care and concern toward the people with whom we are in conflict to solve the most difficult, intractable challenges we face. Paul describes agape to the Corinthians in this way:

If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Love [agape] is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs.

Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails. (1 Corinthians 13:3–8)

It takes loving our enemies to mend relationships in our families, overcome gridlock in the workplace, solve deep partisanship in our communities and countries, and problem-solve with our international adversaries collaboratively.

Writes King, “Love is the only force capable of transforming an enemy into a friend. We never get rid of an enemy by meeting hate with hate; we get rid of an enemy by getting rid of enmity. By it’s very nature, hate destroys and tears down; by its very nature, love creates and builds up. Love transforms with redemptive power.”[v]

Love, writes novelist V. S. Naipaul, can lead to liberation from “the prisons of the spirit that men create for themselves and others—so overpowering, so much part of the way things appear to have to be, and then, abruptly, with a little shift, so insubstantial.”[vi]

Jesus ends the parable with a question and then an invitation: “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” The lawyer replied, “The one who had mercy on him.” Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise” (Luke 10: 36-37).

Amy-Jill Levine writes:

Can we finally agree that it is better to acknowledge humanity and the potential to do good in the enemy than to choose death? Will we be able to care for our enemies, who are also our neighbors? Will we be able to bind up their wounds rather than blow up their cities? And can we imagine that they might do the same for us? Can we put into practice that inauguration promise of not leaving the wounded traveler on the road? The biblical text—and concern for humanity’s future—tell us we must.[vii]

From exile to return. From brokenness to healing. From conflict to peace.

To quote Leonard Cohen from his beautiful song Anthem

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack, a crack, in everything.

That’s how the light gets in.

Following Jesus’s advice is the foundation for truly transformative conflict work. So, how do we love our enemies when the eyes of our hearts when are closed by fear?

Pastor White and I will be in conversation on that exact topic with her congregation and anyone else that would like to attend on Sunday, May 18th at the First Presbyterian Church in SLC at 6 pm.

[i] Martin Luther King Jr., Strength to Love, 46.

[ii] King, Strength to Love, 46.

[iii] King, Strength to Love, 26.

[iv] Adam Miller, Grace is Not God’s Back-up Plan, 29.

[v] King, Strength to Love, 48.

[vi] V. S. Naipaul, “How the Land Lay,” The New Yorker, June 6, 1988, 105.

[vii] Amy Jill-Levine, Short Stories by Jesus, 105.

It is a great book! Thanks for a wonder post Chad!

Can I ask — how do we teach these principles at a young age — say in a classroom? We have international teachers who are being persecuted and being told by students as young as Kindergarten to go home. It wears down the persecuted and is difficult not to internalize.