Drying the Tears of our God

We live in a world where there are many reasons to lose hope. On Easter, Jesus inspires us to build heaven here with the lost, the broken-hearted, and our enemies. This is how we dry the tears of God.

(The following is a modified excerpt from my new book, Seventy Times Seven: Jesus’s Path to Conflict Transformation).

The Easter Story is a love story.

It is a story that begins before the world was created, extends to our time and goes far into eternity.

It is a story of sacrifice and suffering.

Of brokenness and healing.

Of forgiveness and renewal.

Of exile and return.

A promise that all things can be restored— in this life and in the world to come.

It is a story of a love that is universal, altruistic and dangerous.

It is a story that not only tells us how we may gain entrance into the next world, but also how we can reconcile with each other to make this world a better one.

It is a story that should forever help us understand John’s most poignant phrase in scripture. “God is love,” (1 John 4:16). And love is a relationship. A relationship of joy that can’t be contained. It is an invitation into that relationship with God and each other, the one at the center of the universe.

God Weeps

To understand the love story we have to back 5000 or so years to an encounter between God and Enoch found in a piece of LDS scripture called the Pearl of Great Price.

God has just worked with Enoch to create Zion — the first time on earth where everyone in the city was of one heart, one mind and where there were no poor among them. Zion was so precious to God that he took it up into heaven. However, most of the world had not joined Zion so God shows Enoch the residue that remains.

“And it came to pass that the God of heaven looked upon the residue of the people, and he wept; and Enoch bore record of it, saying: How is it that the heavens weep, and shed forth their tears as the rain upon the mountains?

And Enoch said unto the Lord: How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity?” (Moses 7: 28-29)

God’s answer?

“The Lord said unto Enoch: Behold these thy brethren; they are the workmanship of mine own hands, and I gave unto them their knowledge, in the day I created them; and in the Garden of Eden, gave I unto man his agency;

And unto thy brethren have I said, and also given commandment, that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood.” (Moses 7:32-33).

God points out the central problem of our existence — our inability to tie love of God to our love of each other. Enoch was shocked to see the effect of our inability to love each other on God. The mistreatment, violence, hatred and prejudice we practice toward one another hurt God. To the point he weeps.

God is not some disinterested despot. He’s a loving father. He loves his children. He wants our happiness. But we hate each other and cause so much suffering. If you’ve ever had children, you know that nothing hurts more than to see your children suffer. Perhaps this is why the philosopher Nietzsche once remarked, “Even God hath his hell: it is his love for man.”[i]

From Jerusalem to Calvary

Jesus comes into the world that Enoch sees several thousand years later to change all of that.

To end enmity.

In Jesus’s day, people had been taught that God loved them, but hated their enemies – whether they be sinners, Romans or Samaritans. The people of Israel felt the yoke of oppression around them and looked for Messiah that could liberate them.

Jesus’s response to conflict was entirely different from what most of his followers expected.

At the beginning of his ministry, Jesus returns to his hometown to deliver his first sermon at his local synagogue. Jesus declared the true nature of his messianic role as the Prince of Peace in Nazareth. Shocked, some of the people of Nazareth respond by trying to throw him off a cliff.

In Luke, Jesus goes to his local synagogue and as was custom, chooses a passage of scripture to read. He opens a scroll to the opening passage of Isaiah, chapter 61.

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, To preach the acceptable year of the Lord. (Luke 4:18–19 KJV)

Jesus’s people were looking for a military commander who lead them out of bondage, Jesus, instead wanted to lead people out of the bondage of hatred. He knew the solution to all of our problems —in this life and in the next — were related to how we saw each other.

Instead of a militant Messiah who would strike down their enemies, the people of Israel got a Messiah who preached that the way to liberation was love, not hate. They got a Messiah who, even on the cross, would live the very words he was asking his disciples to follow. “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34).

Jesus spoke of peace, hope, justice, forgiveness, and reconciliation at a time when the Israelites were suffering deep, intractable, violent conflict. The Roman Empire was crushing the people of Israel. Many wanted their Messiah to fight their enemies, not love them.

A Messiah preaching “love your enemies” was audacious in all the worst ways. What use did they have for a Messiah who loved Romans and sinners and who would later encourage the people of Israel to turn the other cheek and tell them to forgive their enemies four hundred and ninety times?

The audacity of Jesus’s message continued for the rest of his three-year ministry. He taught people how to create heaven here, in this broken, violent, conflict-riddled world. Jesus spent his ministry with the poor, the destitute, and the outcasts. He mended the broken-hearted, delivered those in captivity, healed the blind, and set free those in captivity.

But nowhere is this audacious message of love greater than in the last week of Jesus’s life. In the final few days of his mortal ministry, Jesus gave the world his model for peace. He offered us a way out of the hatred, pain, and sorrow endemic in his time and ours. He calls us to become peacemakers despite our propensity to destructive conflict.

He believes we can change.

The question is, do we believe him?

The Stones Will Cry Out

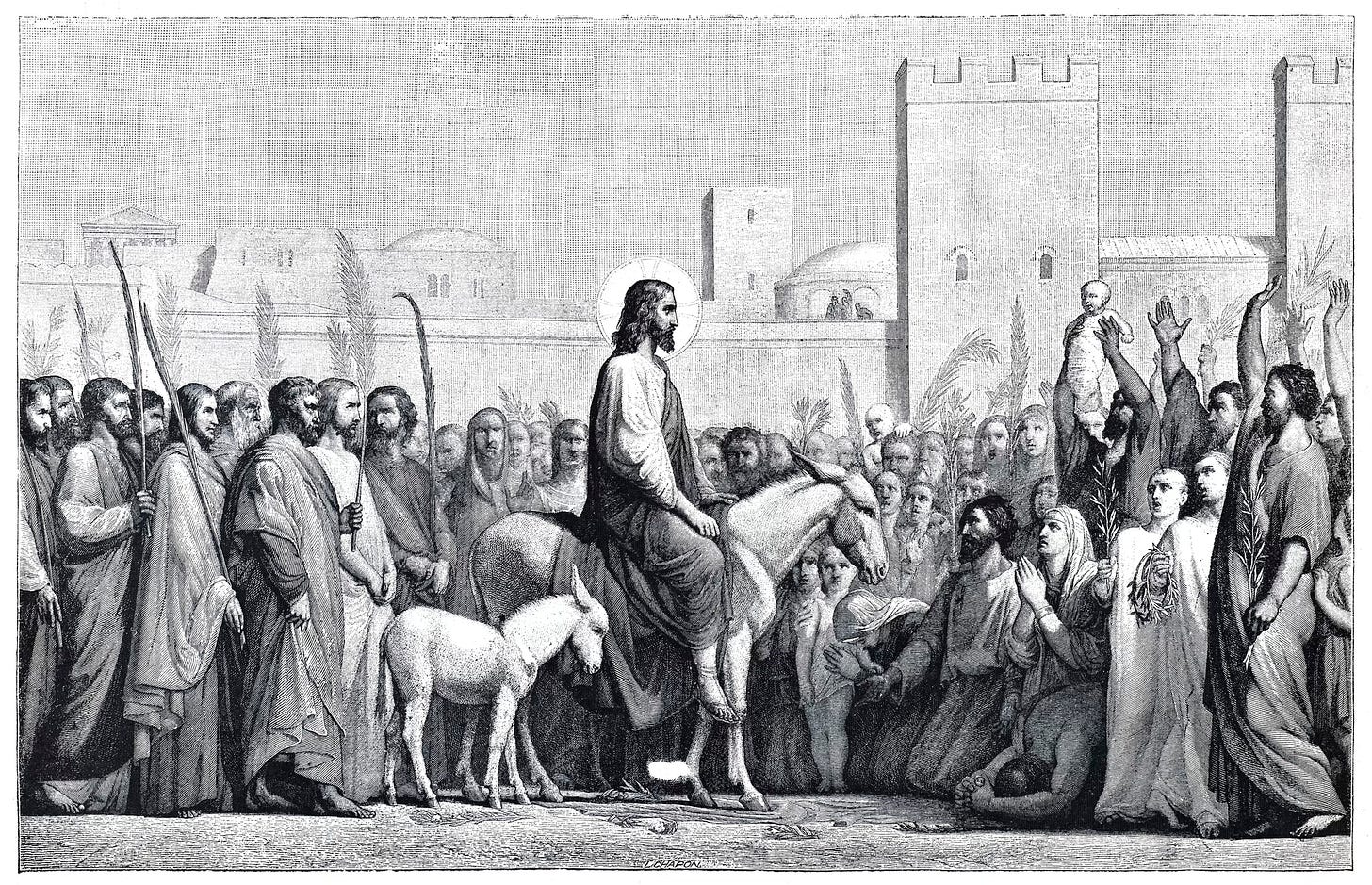

Jerusalem was thronged with pilgrim crowds on the eve of Passover. Many were waiting in anxious anticipation of Jesus. Jesus has just raised Lazarus from the dead. His fame and talk that he might be the Messiah had spread so far that the crowd began working themselves up into a frenzy before he reached the city's gates.

Onlookers spread garments and cast palm fronds, carpeting the way for the passage of a King. As he approached, riding on the back of a donkey, they shouted: “Blessed be the King that cometh in the name of the Lord. Peace in Heaven, Glory in the Highest!” (John 12:13). They cried, “Hosanna,” which translates into, “save us now.”

Jesus could hear the commotion still far from the walls of the city. A weeping Jesus entered the gates of the city to the throng (Luke 19:41). Jesus’s opponents grew more urgent, saying, "The whole world has gone after him!” (John 12:19). The scene made the religious authorities of Jerusalem so uncomfortable that they asked Jesus to calm down the masses.

Jesus responded, “If they keep quiet, the stones will cry out” (Luke 19:40).

If ever there was a time for the “military messiah” to emerge it was now. The people were behind him. If the Messiah was going to save us through violence, this was his chance.

The apostles thought, according to Luke, “that the Kingdom of God would immediately appear” upon Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Instead, they were following Christ to the cross and ultimately to the empty tomb.

Jesus knew what was coming and his heart was heavy. “Now my soul is troubled, and what shall I say? ‘Father, save me from this hour’? No, it was for this very reason I came to this hour” (John 12:27).

After Jesus entered Jerusalem, the apostles prepared for the annual Passover feast. As Jesus entered the feast, the apostles were bickering among themselves. After three years of spending every waking moment by Jesus’s side, many of his teachings still had not sunk deeply into their hearts. Jesus had taught, “The greatest among you will be your servant” (Matthew 23:11). Yet, they argued about who among them was the greatest (John 22:24).

Jesus’s response? He knelt and washed the feet of his apostles. Jesus taught them that if he could lower himself to wash the feet of his followers, they should wash one another’s feet: “No servant is greater than his master, nor is a messenger greater than the one who sent him. Now that you know these things, you will be blessed if you do them.” (John 13:16–17).

After Jesus washed their feet, he held the first sacrament (Matthew 26:26–29). The sacramental prayer Jesus taught in the Americas clarifies the symbolism of the ritual. When we eat the bread, we promise to remember the body of Jesus and take upon us his name. We commit to keep the commandments that he has given us. If we do so, we are promised that we may always have his spirit with us (Moroni 4:3).

After administering the sacrament, Jesus preached his last sermon. With his agony at Gethsemane and the cross at Calvary hours away, Jesus took his last opportunity with his apostles to explain the true nature of his mortal ministry.

A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another. (John 13:34–35)

It would be the first of four times that Jesus would repeat this phrase that night. In his last gathering with his apostles, he tried to distill his ministry so that even a child could understand. Once again, Jesus was calling for us to love each other. There was little doubt that everyone left in the room had a deep love for Jesus. Jesus reminded them, however, that loving the least of these is essential to our continued love of Jesus.

Even while anticipating Gethsemane and Calvary, Jesus lived what he preached. That evening, he had every right to be caught up in his problems and pain. But instead of turning inward to be consumed by despair, he turned outward and comforted his apostles. When Thomas confessed that he was confused about what would happen, Jesus told him, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6).

The Peace We Need

Jesus then promised that though he would leave his apostles' earthly presence, his spirit would always be with them (John 14:15–18, 26). He promised his followers the most elusive of all things in this world: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid” (John 14:27).

It’s not until we understand the context of the events of that wonderful and terrible week that the true meaning of his words becomes clear. Most definitions of peace focus on the external. Security, justice, and the lack of violence or conflict are often considered preconditions to peace. Peace, many believe, comes from the outside in. Instead, Jesus promises peace from the inside out.

True peace, according to Jesus, is rooted in our hearts. But it doesn’t stop there. Inner peace moves outward. Peace is more than a feeling or a state we arrive at. Peace is a verb.

As a mediator who’s worked with thousands of people in conflicts, I can confidently say that most people genuinely want peace. But here’s the catch: when we are mired in conflict, our idea of peace often clashes with the peaceful vision Jesus presented during his ministry.

Jesus offers us an active peace rooted in how we see and act in the world. When experiencing conflict, he calls on us to change. When he calls for justice, he calls for the type of justice that restores, reconciles and makes us whole.

For many of us, the peace we want and call for is passive. We want peace to be a state of being. A feeling. When experiencing conflict, we want someone or something to change for us to find peace. When we call for justice, we call for the type of justice that avenges, punishes, or destroys.

While all of us might hope for a better world, where our lives and relationships are easy, the sort of peace Jesus offers is forged by working our way through destructive conflict.

After promising peace, Jesus talks about the responsibility that comes with the blessings he imparts. If we follow the commandment to love another, we will have joy and all that the Father has (John 15:9–12). And what does that love look like? Jesus explains, “Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. You are my friends if you do what I command” (John 15:13–14).

Here, Jesus teaches us the power of his way of transforming conflict. The peace that Jesus offers comes through living as he did, loving as he loved. Peace comes from loving one another, the stranger, and our enemies as he loved us. After he was done teaching, Jesus knelt with his apostles and prayed to his Father: “I have made you known to them, and will continue to make you known in order that the love you have for me may be in them and that I myself may be in them” (John 17:26). From there, Jesus would depart toward Gethsemane.

Walking the Jericho Road

While visiting Jerusalem, I decided to walk from where Christians commemorate the Last Supper to Gethsemane. I walked approximately twenty minutes down a steep hill. A modern road takes tour buses from one part of the old city to the other. I traveled the much older dirt road that slinks through the valley until it reaches the Mount of Olives.

Walking down the windy, dusty path, I was startled when I reached the bottom to see the road’s name. It was the old Jericho Road. Whether this was the actual path Jesus took that night is impossible to know. But seeing the sign left me with a powerful impression: on the night of atonement in Gethsemane, Jesus was living the parable of the Samaritan in Luke 10. Jesus was walking the Jericho Road.

This time, no “certain man” was lying on the side of the road. Now, humanity lay on the wayside—beaten and bruised by heartbreak and sin. The cost of stopping and helping us would be unimaginably painful. The Samaritan risked being attacked by thieves. Jesus was about to take upon him the sins of the world.

Jesus arrives in Gethsemane. The word is Aramaic origin, from גת שמנא (gath shemanim), meaning "oil press."[ii]According to Luke’s account, Jesus’s anguish would be so great, that “ his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground.” (Luke 22: 44), like the blood red oil that flows from a crushing olive press.

As he reached the Garden and knelt, I wonder if he had a moment, like the people who passed the wounded man on the road to Jericho when they asked, “What will happen to me if I stop to help them?” Perhaps it was when he prayed, “Father, if you are willing, take this cup from me,” (Luke 22:42).

Then Jesus reversed the question. He asked, like the Samaritan that stopped to help the wounded man, “What will happen to them if I do not help them?” He prayed, “not my will, but thine be done.” God couldn’t take this cup from Jesus. It was his alone to drink.

So, Jesus asked his closest friends to help him, to stay awake with him, and to wait with him in his suffering. In his agony, Jesus teaches us how to suffer and the critical role of the Messiah. He tells his apostles, and I’m paraphrasing, “I need you here with me. Can you stand by me while I suffer?”

They fall asleep.

I wonder if there’s a lesson in that vulnerable moment in Gethsemane between Jesus and his apostles for all of us. There are some troubles in life that we can’t take away. When we need to drink from the bitter cup, all we can do is ask for help to bear it. When others need to drink from the cup, we can be the ones who stay awake and help others through it. We can be with the least of these, side by side; mourning with those that mourn; suffering with those that suffer; comforting those that need comfort (see Mosiah 18:10–12).

Sometimes, mourning with those who mourn and suffering with those who suffer is all God will do. Sometimes, it’s all that we can do. But that succoring means something. Mutual suffering ties us together. Selfless love is the antidote to everything wrong with us and the world today.

We weep. We hold hands. We love one another exactly as he loved us. We suffer. We succor. We stay awake. We stay connected to each other in joy and heartache. We find our lives when we lose them in the lives of others. And somehow, the suffering together heals the pain, brings peace, and makes everything new. Writes philosopher Terry Warner:

How can we ever throw off these bands and chains and make things better in this world? May I suggest again: in Jesus’s way. Rather than resisting evil, he suffered. Rather than compromise, he suffered. Rather than rejecting any of us—though every possible provocation to do so was laid upon him—he suffered. He outlasted all these provocations. He conquered the forcefulness of force. He defeated all the pressures that pushed humanity toward enmity and discord.

The Savior seems to say to us: “Come unto me, and I will give you such assurance and hope and strength that you cannot be taken hostage by anyone who seems to do you harm. I will liberate you into love. And then you will no longer give anyone cause to resent or fear you. Instead, they will respond to the love which I have bestowed upon you. By abiding in me, you will do much good, bear much fruit.”

How then shall we come unto Jesus, so that everything will be different from what it could possibly be otherwise? By sacrificing all taking of offense. By giving up criticism, impatience, and contempt, for they accuse the sisters and brothers for whom Jesus died. By renouncing war in every form and proclaiming peace.[iii]

In Gethsemane, Jesus performed the most audacious act in human history. He bled from every pore (Mosiah 3:7, Luke 23:43-44). He took upon himself the infirmities, trials, sufferings, and sicknesses of humankind to succor us completely (Alma 7:11–12). He suffered everything for our comfort and peace. While we can never do what Jesus did for others, we can follow his example in transforming conflict with others.

After Jesus’s ordeal in Gethsemane, he is arrested by Roman soldiers. Peter draws his sword and cuts off a soldier’s ear in an attempt to defend Jesus. Instead of praise, Peter gets a rebuke. “Put your sword back in its place,” Jesus said to him, “for all who draw the sword will die by the sword. Do you think I cannot call on my Father, and he will at once put at my disposal more than twelve legions of angels?” (Matt 26:42)

Peter was still looking for a Messiah that would use God’s power to militarily deliver them from bondage. Jesus had consistently taught that love was a force more powerful and the only way to deliver us from the bondage of sin and human disconnection. Fighting back, running away, freezing, these are the common approaches to conflict.

Jesus would do none of these, and neither should his apostles. Jesus’s way is the gospel of “love and peace, of patience and long-suffering, of forbearance and forgiveness, of kindness and good deeds, of charity”[iv] in a world often filled with hatred and war, impatience and victimization, impulsiveness and resentment.

In the next twenty-four hours, Jesus was betrayed by friends, arrested, and sentenced to death, whipped, and beaten, crowned with thorns, and forced to carry his cross. On Golgotha, he died a gruesome death while soldiers gambled for his clothes at the foot of the cross.

Writes Bishop Desmond Tutu,

Jesus knows [suffering] from the inside and has overcome it not by waving a magic wand, but by going through the annihilation, the destruction, the pain, the anguish of a death as excruciating as the crucifixion. That seems to be the pattern of true greatness that we have to undergo to be truly creative … religion is what you do with suffering, yours and that of others. [v]

Three days later, he rose again, having rolled away the ultimate stone of disconnection and death. Jesus gave us all of that. It’s ours. Can we embrace him the way he embraces us?

An Awakening

After Jesus is arrested, Peter says that he doesn’t know Jesus three times, “I do not know the man” (Matt 26: 72, 74) despite promising Jesus that he would never deny him.

Fear had seized Peter again. If Jesus could be arrested and crucified, what fate would await him and the other apostles? Paralyzed with fear, like the priest and Levite who pass the wounded man on the side of the road leading to Jericho, Peter denies both his mission, his values, and his messiah.

After all the horrors of Calvary, and despite the fact that a resurrected Jesus appears to him and the other disciples as they cower in a room locked from the inside, Peter and the other disciples head back to Galilee, where Jesus first called them, and start fishing.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland imagines Peter’s justification for going fishing this way: “Brethren, it has been a glorious three years… But that is over. He has finished His work, and He has risen from the tomb. He has worked out His salvation and ours. So you ask, ‘What do we do now?’ I don’t know more to tell you than to return to your former life, rejoicing. I intend to ‘go fishing.’”[vi]

In Elder Holland’s re-telling of the story, I think the lines “He has finished His work” and “He has worked out His salvation and ours” are telling. It’s impossible to know precisely what those grieving apostles, who had just witnessed the death of Jesus, were thinking. The situation was unprecedented. However, perhaps one interpretation from Elder Holland’s re-telling is that Peter and the other apostles still misunderstood the gospel primarily in terms of personal salvation instead of restoration. They were saved! What else could Jesus want? After all the horror they endured in Jerusalem, I’m sure fishing sounded great. Jesus’s mission, however, wasn’t finished. The great work of restoration had only begun.

Jesus invited Peter and Andrew to follow him on the same Galilean seashore three years ago. The resurrected Jesus appeared again to his apostles and invited them to continue his work. Standing before a pile of fish, he asked Peter a penetrating question: “Do you love me more than these?” Peter said, “Yes, Lord,” he said, “you know that I love you.” To which Jesus responds, “Feed my lambs.” (John 21:15).

Something changed for Peter and the apostles at that moment on the shores of Galilee. The flawed fisherman, still struggling to grasp the enormity of Jesus's work and love, realized that Jesus had taught them to become fishers of humanity (Matthew 4:19, Mark 1:17). Love, not the sword, is what will usher in the Kingdom of Heaven.

And what Peter and the apostles do next will change the world, will upend the Roman Empire, and will open up the path for all of us to practice the ministry of reconciliation. (2 Corinth 5:18).

Jesus's invitation to reconciliation is as urgent for us today as it was for those Galilean fishermen turned disciples.

The Love That Dries God’s Tears

Jesus’s new definition of love is the key to transforming the conflicts that rage in our world. It is a love that is universal, a love that applies to everyone, every race, every religion, male and female, sinner and saint.

It is a love that is selfless, seeks not its own, loves for the sake of love, not gain (1 Corinthians 13:4). It is a love that is dangerous, pushes us out of our comfort zone, and asks us to make peace with our enemies.

We live in a world where there are many reasons to lose hope. Families are crumbling. Fathers and mothers are estranged from each other and their children. Millions of refugees are fleeing war and poverty. Political leaders incite fear and violence towards those who seem different. They fight darkness with darkness and hatred with more hate. It is easy to be discouraged. However, sometimes, it takes one thing to give us hope amid darkness. Jesus’s love defeats hate. His light overcomes darkness. In him, all things can be made new.

Jesus inspires us to build heaven here with the lost, the broken-hearted, and even our enemies.

This is THE love story.

This is how we dry the tears of our God.

[i] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for Everyone and No One (New York: Penguin Classics, 1963), 96.

[ii]Strong’s Greek : 1066. https://biblehub.com/greek/1068.htm

[iii] Terry Warner, “Honest, Simple, Solid, True,” Brigham Young University devotional, January 16, 1996.

[iv] “Message of the First Presidency,” Annual Conference Report, April 1942 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1942), 90.

[v] Michael Battle, Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology of Desmond Tutu (Pilgrim Press, 3rd Ed, 1997), 6.

[vi] Jeffrey R. Holland, "The First Great Commandment," General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, October 2012.